Once there were three sisters who lived alone in a cottage in the woods. They had been there as long as they could remember, and they never saw anyone else.

Now, the oldest sister was no different from other people. Her name was One‑Eye. She had just one eye, right in the middle of her forehead.

The middle sister was also quite ordinary. Her name was Three‑Eyes. She had one eye in her forehead, and one on each side of her face.

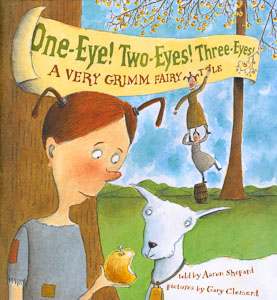

But the youngest sister was different. Her name was Two‑Eyes, and that’s just what she had.

Because Two‑Eyes was not like others, her older sisters were ashamed of her and picked on her all the time. They dressed her in ragged hand-me-downs and only let her eat leftovers.

Now, the sisters owned a goat, and every day Two‑Eyes took it to the meadow to graze. One morning, when she’d had hardly anything to eat, she sat in the grass and cried her two eyes out.

All at once, an old woman stood before her. But the biggest surprise was that this woman had two eyes, just like Two‑Eyes herself.

“What’s wrong, my dear?” asked the woman.

“It’s my sisters,” Two‑Eyes told her. “They never give me enough to eat.”

“Don’t worry about that!” said the woman. “You can have as much as you like. Just say to your goat,

‘Bleat, goat, bleat.

And bring me lots to eat!’

Then you’ll have plenty. When you don’t want any more, just say,

‘Bleat, goat, bleat.

I’ve had so much to eat!’

Then the rest will vanish. Just like this.”

And the old woman vanished—just like that.

Two‑Eyes couldn’t wait to try. She said to the goat,

“Bleat, goat, bleat.

And bring me lots to eat!”

The goat bleated, and a little table and chair appeared. The table was set with a tablecloth, plate, and silverware, and on it were dishes and dishes of wonderful-smelling food.

“This sure is better than leftovers!” said Two‑Eyes.

She sat down and started in hungrily. Everything tasted delicious. When she’d eaten her fill, she said,

“Bleat, goat, bleat.

I’ve had so much to eat!”

The goat bleated and the table vanished. “And that,” said Two‑Eyes, “is better than cleaning up!”

When Two‑Eyes got home, she didn’t touch her bowl of leftovers. Her sisters didn’t notice till she’d gone off to bed. Then Three‑Eyes said, “Look! Our little sister didn’t eat anything!”

“That’s strange,” said One‑Eye. “Is someone else giving her food? I’ll go tomorrow and watch her.”

Next morning, when Two‑Eyes started out, One‑Eye said, “I’m coming along to make sure you tend the goat properly.” Then she followed Two‑Eyes to the meadow and kept a careful eye on her. So Two‑Eyes never got to use the old woman’s rhyme.

When they got home, Two‑Eyes ate her bowl of leftovers. Then she went off to the woods and cried her two eyes out.

The old woman appeared again. “What’s wrong, my dear?”

“It’s my sisters. The goat can’t bring me food, because One‑Eye is watching me.”

“Don’t worry about that!” said the woman. “You can stop her if you like. Just sing her this song.

‘Is your eye awake?

Is your eye asleep?

Is your eye awake?

Is your eye asleep?’

Keep singing that, and she’ll sleep soon enough.”

Then the old woman vanished.

Next morning, when Two‑Eyes went to the meadow, One‑Eye again went along. Two‑Eyes said, “Sister, let me sing to you.” And she sang to her over and over,

“Is your eye awake?

Is your eye asleep?

Is your eye awake?

Is your eye asleep?”

One‑Eye’s eyelid began to droop, and soon she was fast asleep. Then Two‑Eyes said to the goat,

“Bleat, goat, bleat.

And bring me lots to eat!”

The goat bleated, the table appeared, and Two‑Eyes ate her fill. Then she said,

“Bleat, goat, bleat.

I’ve had so much to eat!”

The goat bleated again, and the table vanished. Then Two‑Eyes shook her sister, saying, “Wake up, sleepyhead!”

When they got home, Two‑Eyes didn’t touch her leftovers. After she’d gone off to bed, Three‑Eyes asked, “What happened?”

“How should I know?” said One‑Eye. “I fell asleep. If you think you can do better, then you go tomorrow.”

So next morning, when Two‑Eyes went to the meadow, Three‑Eyes went along and kept three careful eyes on her. “Listen,” said Two‑Eyes, “and I’ll sing to you.” And she sang to her, over and over,

“Is your eye awake?

Is your eye asleep?

Is your eye awake?

Is your eye asleep?”

As Two‑Eyes sang, the eye in her sister’s forehead went to sleep—but her other two eyes didn’t! Three‑Eyes pretended, though, by closing them almost all the way and peeking through. She couldn’t quite hear what Two‑Eyes told the goat, but she saw everything.

That night, when Two‑Eyes had gone off to bed, One‑Eye asked, “What happened?”

“Our sister knows a charm to make the goat bring wonderful food,” said Three‑Eyes. “But I couldn’t hear the words.”

“Then let’s get rid of the goat,” said One‑Eye. And they drove it off into the woods.

Next morning, One‑Eye told Two‑Eyes, “You thought you could eat better than your sisters, did you? Well, the goat is gone, so that’s that.”

Two‑Eyes went down to the stream and cried her two eyes out. Again the old woman appeared. “What’s wrong, my dear?”

“It’s my sisters. The song didn’t work on Three‑Eyes. She saw everything, and now they’ve chased away the goat.”

“Silly girl! That charm was just for One‑Eye. For Three‑Eyes, you should have sung,

‘Are your eyes awake?

Are your eyes asleep?’

But don’t worry about that. Here, take this seed and plant it in front of your cottage. You’ll soon have a tall tree with leaves of silver and apples of gold. When you want an apple, just say,

‘Apple hanging on the tree,

I am Two‑Eyes. Come to me!’

It will fall right into your hand.”

Again the old woman vanished. Two‑Eyes went home and waited till her sisters weren’t looking, then dug a small hole and planted the seed.

The next morning, a tall tree stood before the cottage with leaves of silver and apples of gold. Two‑Eyes found her sisters gaping at it in astonishment.

All at once, Three‑Eyes cried, “Look! A man!”

Riding toward them was a knight in full armor, his visor over his face.

“Quick!” said One‑Eye. “Hide our little sister!” So they lowered an empty barrel over Two‑Eyes.

“Good morning, ladies,” the knight said as he rode up. “Beautiful tree you have there. I would dearly love to have one of those apples. In fact, I would grant anything in my power to the lady who first gave me one.”

The two sisters gasped. They scrambled over to the tree and jumped up and down, trying to grab the apples. But the branches just lifted themselves higher, so the apples were always out of reach.

Meanwhile, Two‑Eyes raised her barrel just a little and kicked a stone so it rolled over to the knight.

“That’s odd,” he said. “That stone seems to have come from that barrel. Does anyone happen to be in there?”

“Oh no, sir,” said One‑Eye, “not really. Just our little sister.”

“She’s different,” said Three‑Eyes, “so we can’t let anyone see her.”

“But I want to see her,” said the knight. “Young lady, please come out!”

So Two‑Eyes lifted off the barrel.

“My word!” said the knight. “She’s the loveliest young lady I’ve ever seen!” He raised his visor for a better look.

“Oh no!” screamed One‑Eye and Three‑Eyes together. “Two eyes!”

Sure enough, the knight had two eyes, just like their sister.

“Dear lady,” said the knight, “can you give me an apple from that tree?”

“Of course!” said Two‑Eyes. Standing under it, she said,

“Apple hanging on the tree,

I am Two‑Eyes. Come to me!”

An apple dropped right into her hand, and she gave it to the knight.

“My thanks!” he said. “And now I will grant anything in my power.”

“Well, to start with,” said Two‑Eyes, “you can take me away from these horrid, hateful sisters!”

So the knight took Two‑Eyes back to his castle. And since they had so much in common—after all, they both had two eyes—you can be sure they lived happily ever after.

As for One‑Eye and Three‑Eyes, day after day they stood under that tree and repeated their sister’s words.

“Apple hanging on the tree,

I am Two‑Eyes. Come to me!”

But the apples never fell for them, and they never did figure out why.

Tips for Telling

Before I first told this story, I wondered whether it was too long, quiet, and involved to hold the attention of a young audience. I was agreeably surprised to find that young listeners are fascinated by it. They’re so busy following its twists and turns, they lose themselves completely. Just be sure to give them time to do it. This is definitely a story you don’t want to rush.

It’s easy to establish a link to your listeners with this one. Before the story, I just ask, “Who has a sister?” And then, “Who has trouble with a sister?” The second show of hands isn’t much smaller than the first. Then I tell them this is a story about a girl who has trouble with her sisters.

For characters, I like to make One‑Eye stern and grumpy, while Three‑Eyes is alert and excitable. I hate to say it, but Two‑Eyes really is a kind of a wimp, at least till the end. To counterbalance that, you might want to take it to an extreme and make her a bit comical, with exaggerated crying, sobbing, and whining.

There are some good opportunities for mime in this one. When you first introduce the sisters, you can point to where their eyes would be on your own face. With the seed, you can mime the old woman handing it to Two‑Eyes and her taking it and later planting it. For the tree, you can use your arms to show how the branches raise and lower themselves to stay out of reach of the older sisters. When Two‑Eyes is in the barrel, you can scrunch a bit, then lift the barrel with your palm flat against the barrel top while you straighten up, then kick.

There’s also much good mime related to apples. When the old woman first tells Two‑Eyes about an apple falling, you can hold out your hand, palm up, and mime the apple landing in it—letting it drop a bit under the apple’s “weight” and then rebounding. The exact same motion can be used when Two‑Eyes actually catches the apple—though in that case, you also want to show her watching the apple as it falls. Then there’s Two‑Eyes handing the apple to the Knight, and him taking it. For humor, I like to have him take a big bite of it and then talk with his mouth full.

You don’t need to worry about how well you sing on this one. It doesn’t have to sound pretty, and your listeners will be focused on the words.

Because my young listeners are working so hard to figure things out, I often given them the chance to test themselves. When I get to the part where Two‑Eyes sings to Three‑Eyes, I follow the song by asking, “What do you think happened?” I usually keep taking answers till someone gives me the right one, but I don’t confirm or deny, only saying, “OK, let’s see what happened.”

Of course, I don’t interrupt the flow of the ending to see who can tell me why no apple falls for the sisters—and I don’t necessarily want everyone to know right away. I figure that the ones who understand will at some point clue in the ones who don’t. Sometimes a poor young soul just can’t contain himself, though, and bursts out, “I know why!” Then I have to studiously ignore him. (Yes, it’s usually a “him.”)

I seldom add anything to a story once it’s done, but for this one I make an exception. I tell my listeners they could use the old woman’s song on themselves if they have trouble sleeping—but they have to sing the right words. “Do you know what they are?”

Usually someone works it out, but it can take a while. The answer of course is, “Are my eyes awake, are my eyes asleep.”