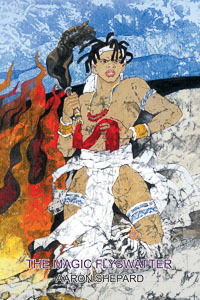

The storyteller stands beside the fire, swaying, dancing, miming, singing, reciting. With one hand he shakes a gourd rattle, with the other he swings a conga—a flyswatter made with a buffalo tail on a wooden handle. Anklet bells tinkle as he moves. Three young men beat a wooden drum with sticks.

Listening to him is a crowd of men, women, and children. They sing along at a song’s refrain, they repeat whole lines of the story when he pauses to see if they’re paying attention. They encourage him with little shouts, whoops, claps. Food and drink are passed around.

In a mountain rainforest of the Congo, a Nyanga village hears once more the tale of its favorite hero—Mwindo, the one born walking, the one born talking . . .

* * *

In the village of Tubondo lived a great chief. His name was She‑Mwindo.

One day he called together his seven wives and his counselors and all his people. He told them, “When a daughter marries, her family is paid a bride-price. But when a son marries, it is his family that pays it. So, all my children must be daughters. If any is a son, I will kill him.”

The people were astonished. But they said nothing, for they were afraid of him.

Soon all the chief’s seven wives became pregnant. The children of six wives arrived on the same day. They were all daughters. But the child of his favorite wife did not arrive.

The child that did not arrive was Mwindo. He was not ready to arrive.

At last he told himself, “I am ready. But I will not come out like other babies. I will come out through my mother’s navel.”

His mother lay in bed. He came out through her navel. He jumped down and ran around the room. In his hand was a conga flyswatter, with a handle of wood and a swatter of buffalo tail.

His mother cried out. “Aieeeeeee! What kind of child is this?”

The baby sang and danced and waved his conga.

I am Mwindo,

the one born walking,

the one born talking.

My father She‑Mwindo does not want me.

My father the chief wants to kill me.

But what can he do against me?

She‑Mwindo heard the noise. He went to the house of his favorite wife. He saw the boy and was full of rage. “What is this? Did I not say ‘no sons’? Did I not say I would kill him?”

He threw his spear at the baby. Mwindo waved his conga. The spear fell short and stuck in the floor. Mwindo pulled it up. He broke it in two.

She‑Mwindo cried out. “Aieeeeeee! What kind of child is this?”

Mwindo sang and danced and waved his conga.

I am Mwindo,

the one born walking,

the one born talking.

O my father, you do not want me.

O my father, you try to kill me.

But what can you do against me?

The chief rushed out. He called his counselors. “My favorite wife has given birth to a son. I cannot spear him. But I can bury him. Dig a grave and put him in.”

The counselors said nothing. They dug a grave. They put Mwindo at the bottom. They threw in the dirt.

The day was done. Everyone went to sleep. The next morning, the chief woke up. He heard a song.

I am Mwindo,

the one born walking,

the one born talking.

My father does not want me.

My father tried to bury me.

But what can he do against me?

The chief rushed from his house. He went to the grave. It was all dug up. He went to the house of his favorite wife. The baby was on her lap.

She‑Mwindo cried out. “Aieeeeeee! What kind of child is this?”

He went and called his counselors. “I cannot spear the child. I cannot bury him. But I can float him down the river. Make a drum and put him in.”

The counselors said nothing. They cut a piece of log and hollowed it. They prepared two antelope hides. They placed the baby inside. They laced and pegged the hides.

The chief took the drum to the river. He threw it far out. He looked to see it float downstream.

The drum did not float downstream. It floated just where it was. The chief heard a song.

I am Mwindo,

the one born walking,

the one born talking.

O my father, you do not want me.

O my father, you send me downriver.

What is downriver?

Nothing for Mwindo!

What is upriver?

Something for Mwindo—

my father’s sister,

my aunt Iyangura.

My father does not want me,

but my aunt will want me.

Mwindo will not go downriver,

Mwindo will go upriver.

Mwindo goes where he wants to go.

The drum floated upstream. She‑Mwindo cried out. “Aieeeeeee! What kind of child is this?” Then he said, “But now he’s gone.” He returned to the village.

Mwindo went upstream. He was going to Aunt Iyangura. He came near her village. He floated his drum to the bank.

The serving girls of Iyangura came to draw water. They saw the drum and heard a song.

I am Mwindo,

the one born walking,

the one born talking.

My father did not want me.

My father tried to kill me.

But Aunt Iyangura will want me.

The girls rushed to tell Iyangura. She came running. With a knife, she slashed open the drum. There was the baby with his conga. Iyangura was astonished. He shone like the rising sun.

Iyangura said, “What a fine boy is Mwindo! How could my brother reject him? Iyangura will not reject him!” She picked him up and carried him to her house. She cared for him.

Mwindo grew up. A day went by, a week, a month, and he was grown. Then he said, “O my aunt, thank you for caring for me. Now I go to fight my father.”

His aunt said, “What is this talk? Your father’s village is huge. He has many men to fight for him. You cannot fight your father.”

But Mwindo sang and danced and waved his conga.

I am Mwindo,

the one born walking,

the one born talking.

My father did not want me.

My father tried to kill me.

Now he must fight me.

His aunt said, “All right, then. But I will go with you.”

Mwindo and his aunt started off. Iyangura brought her servants and the musicians and drummers of her village. They all sang and danced as they went.

They danced to the village of Tubondo. Mwindo danced ahead through the gate. He had no weapon.

The chief said, “Who is this strange fellow? Should we kill him?”

Mwindo sang and danced and waved his conga.

I am Mwindo,

the one born walking,

the one born talking.

O my father, you did not want me.

O my father, you tried to kill me.

Now you must fight me.

Again you will try to kill me.

But what can you do against me?

She‑Mwindo trembled. “O men of Tubondo, throw your spears!”

The men of Tubondo threw their spears. Mwindo waved his conga. All the spears fell short.

She‑Mwindo shook. “O men of Tubondo, shoot your arrows!”

The men of Tubondo shot their arrows. Mwindo waved his conga. All the arrows fell short.

She‑Mwindo quaked. “O men of Tubondo, throw yourselves at him!”

The men of Tubondo threw themselves at him. Mwindo waved his conga. All the men fell down.

She‑Mwindo cried out. “Aieeeeeee! What kind of man is this?”

Mwindo sang and danced and waved his conga.

I am Mwindo,

the one born walking,

the one born talking.

O my father, still you do not want me.

O my father, again you try to kill me.

Your men threw their spears.

Your men shot their arrows.

Your men threw themselves at me.

But what can they do against me?

All the men of Tubondo got up. They said, “What a great man is Mwindo! What can anyone do against you?”

Mwindo stopped dancing. “Where is my father?”

Iyangura came up. “O Mwindo, your father ran out the other gate.”

Mwindo ran from the village. He saw his father. His father ran fast. Mwindo ran faster. Mwindo caught his father. They fell to the ground.

She‑Mwindo trembled and shook and quaked. He said, “Will you kill me?”

Mwindo said, “No, I will not kill you.”

“Will you hurt me?”

“No, I will not hurt you.”

“Will you take what is mine?”

“No, I will not take what is yours.”

“Then what do you want with me?”

Mwindo said, “A father cannot be a father without a son, and a son cannot be a son without a father. You must be my father so I can be your son.”

She‑Mwindo was astonished. “What a wise young man is Mwindo! What a mistake to reject him! No longer will She‑Mwindo reject him. I will be your father, and you will be my son.”

Mwindo sang and danced and waved his conga.

I am Mwindo,

the one born walking,

the one born talking.

O my father, you did not want me.

O my father, you tried to spear me.

You tried to bury me.

You tried to send me downriver.

You set your men against me.

Then you ran away from me.

But how could you escape me?

The son caught his father.

The father faced his son.

Now you are truly my father.

Now I am truly your son.

She‑Mwindo has a son!

Mwindo has a father!

Mwindo and his father returned to the village. Everyone was happy to see them—Iyangura, the counselors, the seven wives of the chief, all the people of Tubondo.

She‑Mwindo told them, “This I have learned: A man must not value only a daughter or only a son. Each is a blessing of its own. What a wonderful son is Mwindo!”

About the Story

The Mwindo epic comes from the Nyanga, one of the Bantu-speaking peoples that live in the mountainous rainforests in the east of the Congo. (A former name of the Congo was Zaire). In the 1950s, when the epic was collected, the Nyanga numbered about 27,000. Traditionally, they are governed by chiefs, each one ruling over several villages.

The Nyanga themselves have no written version of the Mwindo epic, so it has never reached a standardized form. Of the four versions transcribed and published by outsiders, no two are even nearly the same—and no doubt there are many other distinct versions.

The epic is performed as simple entertainment by amateur bards. The bards’ performance includes song and dance, accompanied by drummers and other musicians. Only a portion of the epic is performed at a time, as a complete performance would take too long. (My retelling itself includes only a part of Mwindo’s adventures.)

Following are notes on particular elements of the story.

Mwindo. The Nyanga do not seem to claim Mwindo as a historical figure, and there is no reason to believe he was one. The name itself has no remembered meaning, but it is now commonly given to a son born after many daughters.

She‑Mwindo. The name means “father of Mwindo”—so, of course, it could not really have been his name when the story starts!

Bride-price. In most of Africa—and in many other cultures worldwide—it is the custom for a groom and his family to send a substantial wedding gift to the family of the bride. This is basically the reverse form of “dowry,” a custom that is common elsewhere. Names for the gift include “wooing present,” “bride-price,” and “bride-wealth.” Where this is practiced, the birth of many sons can impoverish a family, while the birth of many daughters can enrich it.

Conga. This is a flyswatter with a scepter‑like handle of wood. The swatter attached at the top can be leaves, an antelope tail, or, as in this story, the tail of a Cape buffalo. A conga is included in the regalia of a chief, and so signifies here the destiny of Mwindo, who will become chief after his father.

Though this retelling is in my own words, I’ve done my best to retain the flavor of the original. Sources for the retelling were:

The Mwindo Epic: From the Banyanga (Congo Republic), edited and translated by Daniel Biebuyck and Kahombo C. Mateene, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1969. (Banyanga means “the Nyanga people.”)

Hero and Chief: Epic Literature from the Banyanga, Zaire Republic, Daniel P. Biebuyck, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London, 1978.

How to Say the Names

These pronunciations are only approximate. To be more accurate, say all vowels as in Spanish or Italian. The letter o, for example, is halfway between a long and short o. The letter e is halfway between a short e and a long a.

conga ~ KOHNG‑gah

Iyangura ~ EE‑yong‑GOO‑rah

Mwindo ~ MWEE‑’n‑do

She‑Mwindo ~ shay‑MWEE‑’n‑do

Tubondo ~ too‑BO‑’n‑do